Fascinating Psalm 2 – Part 4 © Johannes Gerloff

The God revealed to us by the Bible is not just sitting in heaven, smiling about the events on planet Earth. He interferes. The prophetic psalmist of Psalm 2 forsees a time when God speaks up, audibly, understandably, unequivocally, unmistakably.

“Then He shall speak to them in His wrath. In His fury He will terrify them” (Psalms 2:5). God does not state objectively, from a distance, neutrally or even scientifically what might happen. He gets emotional, terrifyingly emotional.

Amos Hakham[1] hears in the language of this verse “a warrior of flesh and blood. First, he mocks his enemy, who is weaker than himself. Then he proceeds with fury against him to fight and destroy him.”[2] Rashi[3] refers to the “rage of fury” in the “Song of the Sea” (Exodus 15:8), and Hakham adds, “that one actually hears the snorting of the nose in this language. When a person is angry, he actually ejects breath through his nose.”[4] This is audible in the Hebrew word for nose, “af” (אף), which is used here.

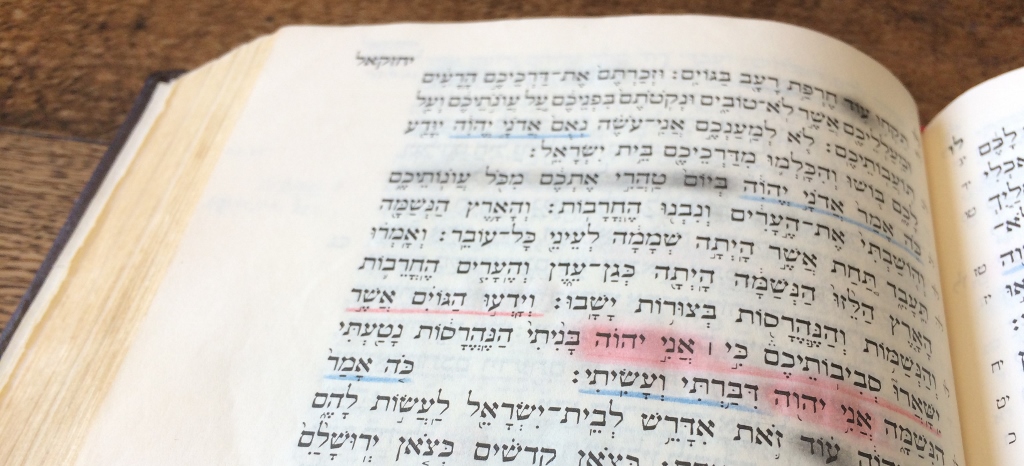

The Bible testifies of the word of God: He speaks and it happens. “He calls and everything stands there” (Isaiah 48:13). It quotes the living God several times with the words: “I say it and I will also do it.”[5] Even the Hebrew word stem used in Psalms 2:5 to denote God’s speaking does not distinguish between “word” and “thing.” What is being “said” is one and the same as the “thing” it designates. The object enters into being by speaking. The Hebrew word “davar” (דבר) has the meaning “word” as well as “thing” or “object.”

When God speaks, He does not just utter His thoughts. Rather, His word cuts powerfully into the waves of the sea of nations (compare Psalms 2:1-2). When the living Creator God breaks His silence, He can no longer be ignored by His creatures. Then, an energy is being released that makes any human-imaginable nuclear explosion seem insignificant in comparison. God shapes the events in this world through His word.

Samson Raphael Hirsch[6] recognizes in the Hebrew word “to frighten” (bahal/בהל) a relationship with the word “ba’al” (בעל), which is usually translated as “lord,” “husband,” “proprietor,” or “owner.”[7] Originally it refers to the one who has overwhelmed, subjugated and taken possession of another. Hirsch opines, this frightening is about “the overwhelming of the inner being, [it is about] consternation”[8].

Rashi observes that God’s speech is not directed in favor of the nations, but against them. Then he asks: “What is the speech of God actually all about?” Radak[9] answers, some interpreters see a connection between the Hebrew word stem “davar” (דבר) used here for God’s speaking and “the very serious plague” (דֶּ֖בֶר כָּבֵ֥ד מְאֹֽד), which Moses threatens in Egypt in Exodus 9:3. There, the Hebrew word “dever” (דֶּבֶר) appears for “plague,” which is totally identical to “davar” (דבר) without vocalization. The rabbinic teachers further observe that in 2 Chronicles 22:10, it is said of the wicked Israelite queen Atalya “she said” (וַתְּדַבֵּ֛ר), which in reality meant “she killed everyone who belonged to the royal family.” Ibn Ezra[10] summarizes concisely, “This is the language of death!”

While the Jewish interpreters of Scripture have no problem understanding the meaning of these words, Martin Luther gets tangled up at this point.[11] Obviously, the reformer pushes his limits with the one-dimensional Christian interpretation of Psalm 2, focusing exclusively on the suffering, crucifixion, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. He asks, “But when did He speak to them in His anger, or in what did His anger express itself?” Luther considered that these words could have been said “about the Roman army.” But then he completely misses out the possibility that the Romans or their vassal king Herod could have drawn the wrath of God upon themselves for having executed Jesus. It was actually the Roman occupiers who were responsible for the sentencing of Jesus. And they carried out the execution in a way typical for the Roman judicial system, namely as crucifixion. If Jesus had been executed by Jews in a Jewish way, he would have died by stoning, such as Stephen (Acts 7:45ff.).

Luther reveals in this context how biased his interpretation of Scripture is by his anti-Jewish perspective. He concludes here in verse 5, “But the Jews, when they were devastated and slain by the Romans, He terrified them by the onset of fear eternally.” The German reformer thought he had to remind his readers at this point: “Now see the register of horrible punishments prepared for the murderers of Christ.” To conclude then: “No creature, not even God Himself, is inclined to them.”

But back to our text. Being emotionally charged in such a way, what does God say? What is His message to the nations? – “I have set My king on Zion, the mountain of My holiness.” (Psalm 2:6). The British scholar Derek Kidner sees at this point, “this is the neglected voice that has the final say.”[12]

First of all, Psalm 2:6 basically states: God is the One who appoints the rulers of this world and removes them. This was recognized by the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar who confessed to the Jewish Prophet Daniel: “Your God is a God over all gods and a Lord over all kings” (Daniel 2:47). At the same time the Prophet Ezekiel (17:24) testifies in his rich pictorial language, portraying the powerful of the world as trees: “All the trees of the field shall know that I am the Lord: I humiliate the lofty tree. I raise up the humble tree. I cause the fresh tree to wither and the dry tree to flourish. I, the Lord, speak and do it (דִּבַּ֥רְתִּי וְעָשִֽׂיתִי).”

Even prior to the Babylonian exile, the God of Israel had emerged as the actual engine of all ethnic migrations. He had the Prophet Amos (9:7) aligned: “Are you not like the sons of the Cushites, you sons of Israel? Did not I bring Israel up out of the land of Egypt, just like the Philistines from Kaftor and the Syrians from Kir?” Moses already knew that “the Most High gives the nations their inheritance,” and “sets the boundaries of the peoples” (Deuteronomy 32:8).

God’s answer to the rebellion of the nations is the appointment of his Anointed One in Zion. Rashi paraphrases the words of God in the mouth of the psalmist: “Why are you raging? I have appointed him to be prince and king in Zion, the mountain of my holiness.” And Radak refers back to the original historical context of Psalm 2 narrating: “After David had conquered the fortress of Zion, the Philistines gathered in order to fight against him.” Then the Jewish exegete explicates the thoughts of God: “How can they consider of eradicating the kingship of the house of David? Though I made him king and anointed him!”

This scene is reminiscent of Psalms 110:1, where in a psalm “for David” the “prophetic saying of the Lord for my Lord” is transmitted: “Sit at my right hand until I place your enemies at the footstool of your feet.” The text here describes “not just any human being, but the one who ‘is my saint,’ anointed by me with the Holy Spirit”.[13] In this way “both [the son and Zion] were authenticated by God’s promise” (2 Samuel 7:13ff.).[14]

But, “history makes no mention of a king of Israel being anointed on Zion.”[15] Indeed, this statement is difficult to understand if you only have King David or Jesus Christ in mind. Therefore, the repatriation of the people of Israel to Zion and the establishment of a king on Zion in the future must also be considered here. God will do this, even if “the Gentiles are raging.” The return of the people of Israel is preparing the installation of the anointed king on Mount Zion.

With the affirmation “I have set My king on Zion” (Psalms 2:6), any competition to Jerusalem is eliminated. It is not in Geneva, New York, Brussels, Moscow, Berlin, London, Paris, Beijing or Washington that the fate of humanity is decided, but in Jerusalem. At the same time any other claim to power over this city is declared invalid. Neither the League of Nations nor the United Nations, neither the Pope nor the Islamic world have anything to decide what happens to Jerusalem, but only He “who sits in heaven.” This is one of the fundamental statements of Scripture.

The psalmist here does not use the traditional name, “Yerushalayim,” Jerusalem, to refer to the central city on the mountain ridge between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan Valley. He speaks of “Tsion/Zion” (ציון), a term used much more frequently in the Book of Psalms than the name “Jerusalem.”[16]

“Tsioun” (ציון) is a “designation” or “marking,” the “grade” that a student receives at school. “Tsioun LeShevah” (ציון לשבח) is the “award,” a “honorable citation,” “Tsioun-Derech” (ציון-דרך) the “signpost,” the “landmark.” Luther says, “The name Zion designates a control room.”[17] And Hirsch explains “Zion” as a “landmark and monument to humanity.”[18]

“Zion” demands attention and thus gives alignment, provides orientation. Those who are influenced by the biblical word live “Zion-oriented.” That is, they do not orientate themselves according to the great and powerful of this world, neither according to zeitgeist nor “political correctness.” Rather, they look at Zion and know: “Torah, i.e. instruction, will proceed from Zion” (Isaiah 2:3). To live “Zion-oriented” is not just about looking at Zion, but fundamentally about being guided by Zion.

Zion is defined as “mountain of my holiness” or “my holy mountain.” It is God’s holiness that is decisive for the character of this mountain. Zion is the place where the Almighty Creator and Mover of the universe is grounded, mooring to this earth. Paul testifies that the “glory” belongs to the people of Israel (Romans 9:4). The living God has bound His glorious presence, which is called “Shekhinah” (שכינה) in rabbinic teaching, to this nation. And in our time, after millennia of separation, she returns to Zion together with the Jewish people.

Footnotes:

[1] (1921-2012) became known in Israel as champion of the first Israeli and worldwide Bible quiz. His handicapped father, Noah Hakham, was a Jewish Bible teacher who had moved from Vienna to Jerusalem in 1913. He had not sent the only son to a public school for fear of a speech impediment. Rather, he himself had trained him in extremely poor conditions. The Bible quiz in August 1958 revealed Amos’ genius and established his legendary career as interpreter of Scripture.

[2] עמוס חכם, ספר תהלים, ספרים ג-ה, מזמורים עג-קן (ירושלים: הוצאת מוסד הרב קוק, הדפסה שישית תש”ן/1990), ז.

[3] Rabbi Shlomo Ben Yitzchak (1040-1105) or “Rabbi Shlomo Itzchaki,” commonly called “Rashi,” was born in the northern French town of Troyes, studied for ten years in Mainz and Worms, before he returned to Troyes, where he distinguished himself as a judge and teacher. In his last years he witnessed the persecution of Jews during the Crusades. Rashi is one of the extraordinary interpreters of Jewish writings and the very first who explained the Bible and the Talmud comprehensively. His basic concerns were to bring Holy Scripture to the people, to promote the unity of the Jewish people and the theological confrontation with Christianity. Raschi made a sharp distinction between “pshat” (literal interpretation) and “drash” (allegorical interpretation), whereby the pshat gives the rash. His interpretation of Scripture has decisively shaped the reformer Martin Luther. Although his comments are still standard today, he often writes “I do not know”.

[4] עמוס חכם, ספר תהלים, ספרים ג-ה, מזמורים עג-קן (ירושלים: הוצאת מוסד הרב קוק, הדפסה שישית תש”ן/1990), ז.

[5] “דִּבַּ֥רְתִּי וְעָשִֽׂיתִי” in Ezekiel 17:24; 22:14; 36:36; 37:14.

[6] (1808-1888) came from Hamburg and served as Chief Rabbi in Oldenburg, Aurich, Osnabrück, Moravia and Austrian Silesia. As a distinguished representative of Orthodoxy, he was an outspoken opponent of reformist and conservative Judaism. Hirsch attached great importance to the study of all Scripture. From 1851 he was rabbi of the separatist Orthodox „Israelitischen Religions-Gesellschaft“ (“Israelite Religious Society”), engaged in education and published the monthly magazine “Jeschurun”. Hirsch had a great love for the land of Israel, was at the same time, however, an opponent of the proto-Zionist activities of Zvi Hirsch Kalischer. He is seen as one of the founding fathers of the neo-orthodox movement.

[7] Jaacov Lavy, Langenscheidts Handwörterbuch Hebräisch-Deutsch (Berlin, München, Wien, Zürich: Langenscheidt, 7. Auflage 1985), 79.

[8] Samson Raphael Hirsch, Psalmen (Basel: Verlag Morascha, 2. Neubearbeitete Auflage 2005), 9.

[9] Rabbi David Ben Yosef Kimchi (1160-1235), the so-called “Radak”, was the first among the great exegetes and grammarians of the Hebrew language. He was born in Narbonne, southern France. His father died early, so David was brought up by his brother Moshe Kimchi. Radak allowed philosophical studies only to those whose faith in God and the fear of heaven were firmly established. Publicly he dealt with Christians and attacked primarily their allegorical interpretation of Scripture and the theological claim to be the “true Israel”.

[10] Rabbi Avraham Ben Me’ir Ibn Ezra (1089-1164) is one of the outstanding poets, linguists, interpreters of Scripture and philosophers of the Middle Ages. He came from Toledo in then Muslim Spain. Long journeys took him all over North Africa and up to the Land of Israel. He wrote almost all of his books during the last 24 years of his life. While fleeing Muslim persecution of the Jews, he toured Christian Europe at this time. In 1161 his track is lost in French Narbonne. It is known that he died in January 1164. It is unknown where this happened. Rome, Spain or even England are up for debate. As an outspoken rationalist, Ibn Ezra was the first to question Moses’ authorship of the Pentateuch. However, he believed in the prophetic significance of astrological phenomena – something which Rambam firmly rejected as idol worship. Since his works are written in Hebrew, he made accessible to European Jewry the intellectual wealth of oriental-Jewish scriptural interpretation, which is largely handed down in Arabic. Of particular value are his exact grammatical studies, always seeking the original, literal meaning of the text.

[11] For the following compare Johann Georg Walch (hg.), Dr. Martin Luthers Sämtliche Schriften. Vierter Band. Auslegung des Alten Testaments (Fortsetzung). Auslegung über die Psalmen (Groß Oesingen: Verlag der Lutherischen Buchhandlung Heinrich Harms, 2. Auflage, 1880-1910), 265-267.

[12] Derek Kidner, Psalms 1-72. An Introduction & Commentary, TOTC (Leicester/England and Downers Grove, Illinois/USA: Inter-Varsity, 1973), 51.

[13] Johann Georg Walch (hg.), Dr. Martin Luthers Sämtliche Schriften. Vierter Band. Auslegung des Alten Testaments (Fortsetzung). Auslegung über die Psalmen (Groß Oesingen: Verlag der Lutherischen Buchhandlung Heinrich Harms, 2. Auflage, 1880-1910), 268.

[14] Derek Kidner, Psalms 1-72. An Introduction & Commentary, TOTC (Leicester/England and Downers Grove, Illinois/USA: Inter-Varsity, 1973), 51.

[15] C.F. Keil and F. Delitzsch, Psalms 1-35, Commentary on the Old Testament vol.5/1. Translated by Francis Bolton (Peabody, Massachusetts/USA: Hendrickson Publishers, February 1989), 94.

[16] עמוס חכם, ספר תהלים, ספרים ג-ה, מזמורים עג-קן (ירושלים: הוצאת מוסד הרב קוק, הדפסה שישית תש”ן/1990), ז.

[17] Johann Georg Walch (hg.), Dr. Martin Luthers Sämtliche Schriften. Vierter Band. Auslegung des Alten Testaments (Fortsetzung). Auslegung über die Psalmen (Groß Oesingen: Verlag der Lutherischen Buchhandlung Heinrich Harms, 2. Auflage, 1880-1910), 270.

[18] Samson Raphael Hirsch, Psalmen (Basel: Verlag Morascha, 2. Neubearbeitete Auflage 2005), 9, referring to Jeremiah 31:20; 2 Kings 23:17; Ezekiel 39:15; compare Isaiah 2:3; Jeremiah 30:17.