A Story of an Anthem

I am convinced that HaTikvah, our Israeli national anthem is the most beautiful in the world. I confess I am biased but even though I have my personal reasons (please read on), I am not alone in thinking it is the best in the world.

On that rare occasion when Israel wins a gold medal at a sporting event and the flag is raised to the tune of HaTikvah, footage of those three minutes is shared by millions of Israelis on social media. Truth be told, most don’t know, or care, or will even remember, who won what; what is important is that our anthem is being played to the world.

Israelis are known for being tough, yet HaTikvah never fails to bring a tear to even the toughest and roughest of them all. This applies to those who have defended our land in many a war. No matter how tough, all will unashamedly dry a tear from their eye when they hear our anthem. Some would argue that the tears are because the melody is in a minor key. Of over 200 national anthems, only about a dozen are in a minor key. Most are joyful, party-going and march-like. But HaTikvah is not. Yet HaTikvah moves people, not because it is in a minor key.

“Israelis are known for being tough, yet HaTikvah never fails to bring a tear to even the toughest and roughest of them”

The words to our extraordinary anthem were penned by Naftali Herz Imber, a Jewish Hebrew-language poet who was born in today’s Ukraine. Written in the 19th century, it was not intended to be a tune. It was simply a poem about Jewish hope of a future Israel, and the hope of returning to our land after two thousand years. But the poem became an anthem, and one which tells of an endless history, and espouses for an eternal future. HaTikvah is a declaration of facts. It rises to its name by the existence of our past present and future. HaTikvah is a statement that the people of Israel live, and against all odds we are still here.

While the author of the words is not disputed, the origin of the tune has caused speculations for years. There were those who claimed that the tune came from the Czech composer, Bedřich Smetana from his piece, “Die Moldau.” Others were sure that it found its genesis in a work of the Finnish composer Jean Sibelius. But neither are true. Thirteen years ago, due to the historical research of Israeli-born pianist and musicologist Astrith Baltsan, the mystery was solved and the enigma of where the tune came from, was finally laid to rest.

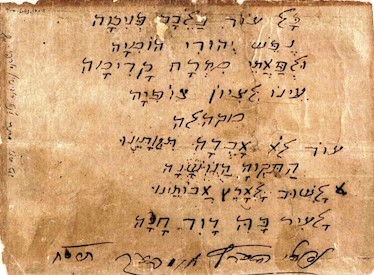

Through her pedantic research, Baltsan discovered that the melody has been a journey that fittingly mirrors that of the Jewish people in the diaspora. Both melody and nation have travelled the world for centuries. Baltsan discovered that the melody goes back 600 years to a Sephardi prayer for dew. In Hebrew, dew is “Tal.” Tal is in our daily prayers. Tal is the consistent, unseen yet nourishing moisture of God on our land and souls, without which we would die.

That is my extra reason for loving HaTikvah. In my very name, it reminds me there is always hope and continued healing.

Songs today by various artists are familiar all around the world. What is true now, was true then. Melodies traveled then and travel today. After the Jewish people were expelled from Spain and Portugal (these are the Sephardim), they took with them their melody for the prayer for dew. The tune lulled its way across land and sea, hummed by people here and there until it eventually found its way to Italy where the tune was set to words. The tune to the Sephardi prayer for dew soon became a popular Italian love song, Fugi, Fugi, Amore Mio which can still be found on Youtube today.

The tune was a hit! It spread and ended up in today’s Moldova, where it was set to a new set of lyrics. This time the original tune for the prayer for dew now hosted the words of a Moldovan gypsy folk song about a cart and oxen.

A Jewish melody in danger of being lost to the Jewish people did not stay lost. Unknown to the Jewish people themselves, that tune for the prayer for dew which became about an ox and a cart, was restored to the Jewish people. Hope was born again. It arose as HaTikvah when 17-year-old Moldovan Shmuel Cohen immigrated to the land of Israel. When Cohen, who knew the Moldovan folk song, came across Imber’s poem in Israel, he decided that there would be no better tune to set it to music to than the Moldovan tune he had heard at home.

It was a perfect fit. Thus, unknown to everyone, the melody had travelled the world mirroring the Jewish journey of the exodus, the dispersion after the destruction of the Temple, the banishment from Spain and eventually the journey of the Jewish remnant who came to the land after the Holocaust.

Like any Jewish story, even a Jewish melody needs a bit of persecution to emphasise the hope. During the 1930’s when the British were ruling the land of Israel, they pettily forbade the Jewish radio station to play HaTikvah. Undeterred and familiar with the similar sounding Smetana’s “Die Moldau,” the radio played that instead. The British could not blacklist a work of classical music, and there was not a Jew in the land who did not read between the lines.

Most moving of all was when HaTikvah was played at the end of World War II. A British Jewish chaplain named Leslie Hardman led Bergen-Belsen Holocaust survivors in a Kabbalat Shabbat ceremony which took place outdoors, in the middle of the horror. It was none other than a choir of human skeletons who found it in them to reach beyond the depths of their despair and sing of the hope from the depths of their brokenness. That gutting performance was recorded by the BBC, yet lay undiscovered for years in the Smithsonian Institute.

But our eternal history has proved that not the British mandate, or the BBC, or the mighty Smithsonian Institute, or the Romans, Babylonians, Egyptians or any other adversary has ever extinguished our hope or our gratitude to God for the טַל [Hebrew: Tal = dew] of the morning where HaTikvah is always found.