Bread Of Days Gone By

There are not too many surprises with the seasons in Israel. The long summers are predictably hot, the winters in the mountains drop to near freezing, and the autumn and spring are short seasons of perfect days in which to celebrate the Jewish festivals. This is because the festivals are determined by the lunar and solar calendar combined, ensuring that the timing of seasons with those of festivals guarantee a successful integration of climate, agriculture and religious life.

In a modern age where technology ensures growth and storage of produce in controlled environments, it is possible to find nearly every fruit and vegetable on the supermarket shelf at any time of year. However, things are different with bread. Unlike fruits and vegetables, grain on a commercial scale cannot be grown in greenhouses. Vast expanses of land are required. Grain farmers always were, and always shall be, at the mercy of the elements to which the land is exposed. Hence, the method for growing grains has barely changed since biblical times.

“Grain farmers always were, and always shall be, at the mercy of the elements to which the land is exposed”

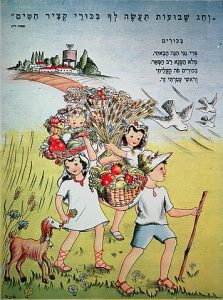

Bread was the main source of food for our forefathers. It was also a part of worship. From the feast of Passover until Shavuot, the People of Israel had to bring an offering of barley (called an Omer) to the Temple. Today, this is commemorated by daily counting the Omer. In Israel during this season today, newsreaders announce what day of the Omer it is. The wheat harvest follows a month and a half later, celebrated by the festival of Shavuot. In Temple times, two loaves were brought up as an offering.

Poster from the late 1940’s depicting the Shavuot (Feast od Pentecost) holiday | Photo: GPO by Unknown

Although several grains grew in the land for thousands of years, barley and wheat were considered the main staple. Bread was sustenance. Bread was so necessary and valuable it was also good for bartering. King Solomon exchanged wheat for cedars in order to build the temple.

It is no coincidence that the Hebrew word for bread, LeHeM, shares the same letters as warrior (LaHaM). This is because making bread was back-breaking work and not just a matter of going to the supermarket as it is today. Strength, persistence and dedication were all needed for making bread. Using a crudely fashioned plow, the farmer needed to break down the hard earth then turn over the soil several times so the weeds would not choke the newly planted seeds. The seeds then needed to be covered again with top soil to hide them from the birds. The harvest included cutting the crops, bringing them to the threshing floor upon which he broke the stalks, tossing them in the air to separate the wheat from the tears, and finally grinding the grain.

But even with a lot of hard work, making bread would be impossible if it were not for the rain from Heaven. Thus, the farmer was very aware that bread was dependent on the mercy of God.

No wonder then, that in Judaism bread is held in high regard. Unlike any other food, bread is eaten at three meals during Shabbat and also on the three Pilgrim festivals. Passover revolves around eating bread – albeit unleavened. The neglect of this commandment lead to dire consequences: exile from one’s people.

“In Judaism bread has the “highest” blessing”

In Judaism, there is a rather complicated but logical way to bless God for food, and the different blessings said before and after eating, are determined by what that food is. Bread has the “highest” blessing. The blessing even has its own name “HaMotzei…” which is a shortening of “He who brought bread from the earth.” Considered so important, bread is the only food which requires the ritual washing of hands before it is consumed.

Following any meal, one of three blessings are said, each varying in length. The blessing after the consumption of bread is the longest and contains many verses from the Bible. A long tradition found in both the Jewish and Arab communities is that of “breaking bread” or sharing a meal. This is done as a gesture of reconciliation after a disagreement and a strengthening of a friendship.

In Israel today wheat fields cover an area of over one million dunams which is 43% of our total farmland. Wheat has been adapted to grow in most parts of the country, from the rainy north to the desert south where rainfall is under 200 mm a year. Every year, the Israeli wheat sector yields approximately 190 thousand tons of grain and 900 thousand tons of straw for animal feed. Although this is impressive, it only amounts to 15% of the national wheat needed for human consumption. The extra has to be imported from abroad.

It’s not just the modern bread found on supermarket shelves which is made in Israel today, the bread of ancient Israel is also being baked in modern times.

On the wall of a little bakery in Kibbutz Einat near the city of Petah Tikva is a black-and-white photograph of a baker, Moshe Rozental, and his wife – Miriam. Moshe and Miriam came from Poland to the Land of Israel in 1870. Against all odds, he grew his business to become one of the most successful bakeries of those times. Five generations later, his offspring is taking up where his ancestors left off and in doing so, Hagai Ben Yehuda is breathing fresh life into Israel’s ancient bread-making traditions.

It has taken a lot of research to produce a bread similar to that eaten in Biblical times. First Hagai began researching emmer, the “mother of wheat,” which was the grain eaten by the People of Israel. About a hundred years ago, Aharon Aronson a Jewish agronomist discovered emmer growing wild near Mount Hermon. A short phone call with Israel’s agricultural research institute, enabled Hagai to obtain some of these Aronson heirloom variety seeds. Not using pesticides, he tested the best ways to prepare, sow and crop with the seasons. In his bakery, flour, water and salt are the only ingredients which make up his biblical sourdough loaves. All have a dark, crumbly crust. Serving the bread with butter, local olive oil or honey, ensures that this modern Israeli baker has drawn a crowd. The Jewish past is inseparable from the Israeli present, and it is bread, that most ancient and “holy” of staples which is urging him to leave his kibbutz and start a bakery in Tel Aviv.