The Iranian Schindler

Abdol Hossein Sardari, an Iranian diplomat stationed in Paris, went to extraordinary lengths to protect Iranian Jews from Nazi persecution. (*)

Born in 1914, Sardari was a member of the distinguished Pahlavi family. He left Teheran as a teenager to continue his education in Europe. In 1925 his family in Iran took control of the country in what was known as the start of the Pahlavi dynasty. In 1936 Sardari graduated in Law from Geneva University in Switzerland and joined the diplomatic service. He was assigned to Iran’s prestigious Paris embassy in 1940, right at the time Hitler invaded.

France was carved up; the Nazis took over the north of the country, and a pro-Nazi French regime under Marshal Philippe Petain took over the south and established its headquarters in the town of Vichy. Most of the Iranian embassy staff fled to the relative calm of the Vichy sector. While the Ambassador, Sardari’s brother in law, returned to Iran, Sardari remained behind as Consul General, heading up a scaled back staff in Paris. In his responsibility as Consul General he was driven by a sense of duty and personal responsibility to assist several hundred Iranian Jews in the city, at risk of Nazi persecution.

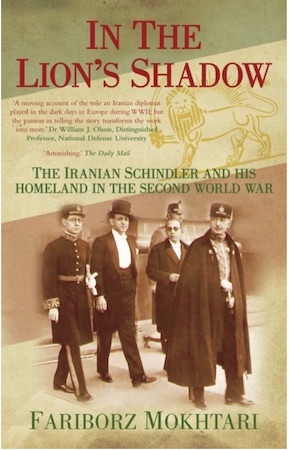

Paris was a popular destination for Iranians at that time, and a sizeable community settled there. Historian Fariborz Mokhtari, whose book ‘In the Lion’s Shadow’ details Sardari’s story, states that the Iranian community was successful in the city. “They celebrated Iranian holidays, some of them owned big luxurious houses and stores.”

Iran was a useful ally for Germany on the Soviet Union’s south-western border. Germany was also Iran’s biggest trading partner. Ties deepened after 1933 following Hitler’s rise to power. In Hitler’s worldview of racial hierarchy, he cultivated the idea that Iranians, like the Germans, had superior blood. This view became policy when, in 1936, Hitler declared Iran to be an Aryan state. This served to massage the egos of Iranian nationalists. Diplomatic and business exchanges continued throughout the years of Hitler’s rule.

Jews had been living in Persia for thousands of years, with the earliest Jewish presence dating to the exile following the destruction of the first temple in 586 BCE. Under the new rule of the Pahlavi dynasty, which had ushered in a wave of modernisation and new reforms, the Jewish community saw greater protection under that dynasty. Reza Shah informed Hitler that he considered Iranian Jews to be fully assimilated Iranians and would take offence to them being blacklisted in any way.

Despite his annoyance, Hitler begrudgingly accepted this, at least in the short term while it was expedient for him that Iranian Jews would not be officially classified as enemies of the Reich.

This move would be exploited to maximum effect by Sardari, now the Consul General in Paris, who eyed an opportunity to protect his countrymen living under German occupation.

One of his first steps was to help Jews hide behind the elevated status given to Iranians in general by issuing new passports which made no reference to their religion. Later he would make the case that although the Jews of Iran did follow some of the traditions of Moses, they had lived in Persia so long and become so assimilated into Persian culture, they were no longer racially distinguishable as Jews. He classified them under a new term, ‘Jugutus’ – a group who followed some Mosaic practices but were not actually racially Jewish.

Backed up with pseudo-scientific research, and playing Sardari (second from the right in glasses) with the Iranian senior staff as they fled Paris in 1940 on Hitler’s machinations towards Iran, as well as wining and dining Nazi officers in the city, Sardari managed to convince several senior Gestapo bureaucrats of his logic. His efforts led to a directive that Iranian Jews in Paris be exempt from wearing the yellow Star of David.

Sardari issued hundreds of passports and forms of documentation for Iranian Jews who turned to him for help. He also helped Jews who weren’t of Iranian descent.

After the war, Sardari had to return to Teheran where he faced disciplinary action for issuing unwarranted Iranian passports. It took him ten years to clear his name, after which he retired from diplomatic service and moved to London where he had family. He died in 1981.

(*Ed.) Fariborz L. Mokhtari wrote a book about Abdol Hossein Sardari that was published in 2013 by The History Press Ltd.

EAN 9780752486383, titled: “In the Lion’s Shadow”.

The book’s cover with Abdol Hussein Sardari second from the right. Sardari was left in charge of the Iranian legation in Paris when the embassy was moved to Vichy.